The Antichrist

Part 2 on Eschatology

Weirdly enough, the antichrist is trending right now in certain circles of the internet. A few months ago, the tech billionaire Peter Thiel gave an interview with Ross Douthat where he shared some of his concerns about where society is going in terms of rising authoritarianism aided by surveillance technology and how that is preparing the way for the “antichrist.” The best part of the interview comes when Ross Douthat asks Thiel if he has ever considered that his own technological investments in mass surveillance technology, weapons systems, and AI might be aiding the rise of antichrist. After all, those seem like helpful tools for such a figure. Thiel is quite obviously taken aback by the suggestion, as if he had never considered that possibility. He hems haws, and denies that is what he is doing and the whole thing is quite humorous. If anything, it’s a perfect example of why we should not entrust our futures to the tech billionaire class. I’ve linked the part of the interview below. To my knowledge, Thiel has since gone on to host a series of lectures about who/what he thinks the antichrist might be.

As I mentioned in my previous post on the rapture, in my early teenage years the Left Behind novels were quite popular and influential in how many of us were taught to think about the second coming of Christ and the “end of the world.” It’s particular interpretation of the Scriptures, a cutting and pasting together of obscure texts to form an “end times” timeline is known as Dispensationalism, and I discussed its origins as well as some of its inherent problems in that earlier post. In addition to teaching that Jesus will one day secretly snatch true Christians out of the world before seven years of judgment (the rapture), this end times schema also sees a figure known as the antichrist seizing global power and establishing an authoritarian system where everyone will have to get microchipped in order to buy or sell (unfortunately, this scenario does not sound quite as far fetched in recent years as it used to, and one has to wonder if folks like Musk and Zuckerberg read these books and got confused on who exactly the bad guy was supposed to be). In light of all this, I want to offer a few of my thoughts on how we should or should not think of “the antichrist.”

The actual word “antichrist” appears only a few times in the Bible, and it’s not in Revelation as many people assume, but in the epistles of John. 1 John 1:18 says, “Children, it is the last hour! As you have heard that antichrist is coming, so now many antichrists have come. From this we know that it is the last hour” (NRSV). Also, 2 John 7, “Many deceivers have gone out into the world, those who do not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh; any such person is the deceiver and the antichrist!” (NRSV). Unfortunately, John doesn’t give us quite as much information as we would like concerning who or what this figure might be. It appears from the rest of John’s letters that there was a group trying to infiltrate his churches who claimed that Jesus did not “come in the flesh” and John identifies this teaching as an “antichrist” teaching. Many scholars point out that John’s descriptions seem to be very similar to an early church heresy known as “docetism” which comes from the Greek word meaning “to appear.” They taught that Jesus only “appeared” to be human, but that he was actually pure spirit, and thus immune to the temptations and suffering that goes along with embodied existence. For John, who had walked with Jesus, eaten bread with him, and touched him, this teaching threatened to undermine the good news of the gospel, that the eternal logos became embodied in a real human being and “dwelt among us” (John 1:14). Those who denied Christ’s humanity were guilty of being “antichrists,” perhaps even prefiguring a future figure or system—it’s hard to tell.

Throughout history there have been various speculations about who or what the antichrist is. Many have identified it with a specific figure. In the ancient world it might be identified with a specific Roman emperor, for example. During the Reformation, Luther famously called the Pope the antichrist, and some Lutheran confessions even embedded that claim. Often, the antichrist has been associated with the impending end of cosmic history and the second coming of Christ, no doubt based on 1 John 1:18. The Left Behind novels and the theology they draw upon certainly do take that approach and like many of their predecessors, create a scenario where current world events enable an authoritarian figure to arise and implement a system that deceives the world by promising peace and prosperity in exchange for absolute loyalty.

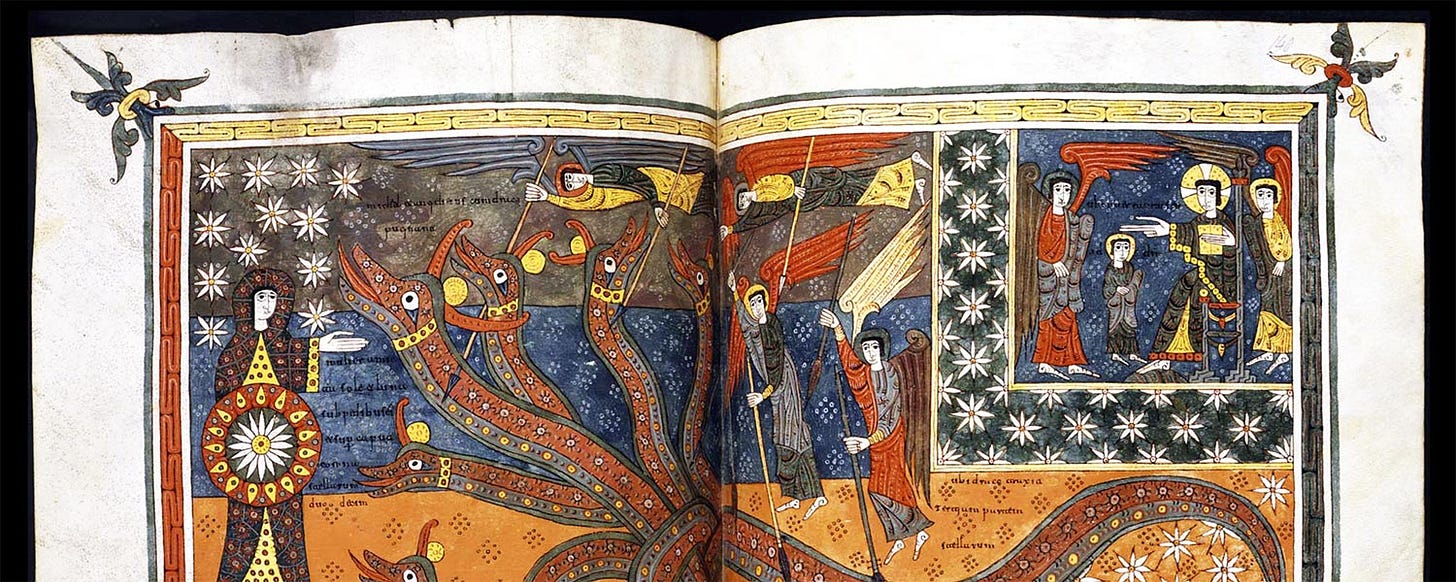

When most people think of the “antichrist,” the book of Revelation reflexively comes to mind, though as I mentioned above, the word itself only appears in the epistles of John. Revelation presents two “beasts,” one rising from the sea and the second from the earth; together, they deceive the world, persecute God’s people and force everyone to receive the first beast’s mark in order to buy or sell (Revelation 13). The beasts and the kings of the earth gather their armies to make war against Christ, but are defeated and cast into “the lake of fire that burns with sulfur” (Revelation 19:17-21). The first beast has frequently been identified with the antichrist figure whom John refers to in his epistle as one who “is coming.” Perhaps.

Dispensationalism, the theology “behind” Left Behind, would have us believe that the book of Revelation is entirely future-oriented, that is, predictive of things to come. This idea has become so baked into American evangelicalism, that many people don’t know there is any other way to understand Revelation. To be sure, there are elements of Revelation that are future events, such as the second coming of Christ and the union between the new heavens and new earth, but that’s simply not the case for most of the book. When one looks at Revelation through the lens of history and compares its literary genre with other similar texts floating around in the late first century, it becomes very clear that most of Revelation is actually dealing with events of the first century.

Not to get too far off track, but the book of Revelation is a letter to seven specific churches. The message it contains is a message that those seven churches needed to hear. If it were entirely a prediction of twenty-first century events, then the text would be absolutely meaningless to those seven churches as well for all Christians until the present time (or whenever time it is supposed to apply to). In addition to its form as a letter it also belongs to a genre known as apocalyptic. Despite its common usage, “apocalyptic” doesn’t mean the “end of the world” but simply means an “unveiling.” The apocalyptic literature that was quite common at the time Revelation was written was a genre that aimed to explain what was happening in the present from the perspective of what God was doing. It naturally used highly symbolic language for everything, but many people would get the cultural clues to understand who or what it was referring to. The book of Daniel contains some elements of apocalyptic literature, as does Zechariah, but Revelation is the most prominent example that has been included in the Protestant Canon of Scripture. Interestingly, until about the 4th century, many churches were unsure of whether Revelation should be regarded as sacred Scripture, and even at the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther regarded Revelation’s status as scripture as questionable. For the record, I do think Revelation is inspired Scripture and has many valuable things to teach us, but I do see why some early Christians had their reservations—the book is strange and hard to understand.

As apocalyptic literature, Revelation uses highly symbolic imagery to convey its message, and this is very apparent when we look at the figure of “the Beast,” whether or not this should be entirely conflated with the antichrists of John’s epistles. I have to pause here and mention that Dispensationalists love to brag about how literally they take the Bible, and especially the book of Revelation. Yet, that’s not the flex they think it is, as the kids say nowadays. Apocalyptic literature simply was never supposed to be read literally. The good news is, despite their protestations to the contrary, I have yet to come across a Dispensationalist who actually does read Revelation literally. The Beast is a prime example, because no Dispensationalist actually thinks there will one day be a real beast with ten horns and seven heads that crawls out of the sea and seizes all earthly power. They instinctively interpret this symbolically as a future world leader, which is absolutely not a literal reading of the text. They are at least partly on the right track.

The identity of the beast of Revelation is actually given away at the end of chapter 13, and it is most likely the emperor Nero. When the writer says “let anyone with understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a person. Its number is six hundred sixty six” (Revelation 13:18), he is employing a tactic known as gematria, a common code in ancient literature where one was expected to figure out the identity of a person by using numbers which corresponded to letters in their name. The greek letter values for 666, if transliterated into Hebrew give us “Nero Caesar.” This is further attested because varying texts of Revelation where the number is not 666, but 616 which also corresponds to Nero, except in Latin. Nero, of course, in addition to being a paranoid, incestuous narcissist, was a notorious persecutor of Christians known for using them as human torches to light his parties.

At this point, historically astute readers might be saying, “Hold on, wasn’t Nero already long dead by the time Revelation was written?” The answer is yes. Nero killed himself in AD 68, and the vast majority of scholars believe that Revelation was written sometime around AD 90, likely during the reign of Domitian. but certainly after Nero was dead. So why would the writer refer to Nero as the beast? Most likely, the author is using Nero as an archetype of the imperial system that persecuted believers and set itself in opposition to Christ. Nero was the worst of the worst, in other words. He was so bad that after his death a conspiracy theory of sorts sprung up around him that suggested he was not actually dead, but had fled east and was going to come back to seize his throne with the help of the Parthian armies (this may be the reference to the beast having a deadly wound that was healed). However, Domitian, the emperor at the time of Revelation’s writing was also a pretty horrible ruler, and had a reputation as sort of a Nero 2.0. In other words, “the beast” is likely the whole Roman imperial system, rather than just a specific individual. Early interpreters of Revelation, such as Irenaeus in the second century, understood that this was very likely referring to Roman emperors.

So what does this mean for us, today if the beast of Revelation might not be code for a present day United Nations leader as the authors of Left Behind seemed to think? If the beast of Revelation is understood as more of an archetype than a singular individual then it actually has quite a bit to say to us, as well as all readers in all times. See, the major weakness of a Dispensationalist reading of Revelation is that the book becomes code for future events at a particular time and then has absolutely no relevance for people living in any other time beyond attempting to decode what it might be “predicting” and whether or not we are living in that particular time when it’s applicable. However, I believe Revelation carries a message, not just to the original seven churches to which it was addressed, but to all Christians at all times, and it’s not to give us a timeline of future events, but is a challenge to live faithfully in a world that is always under the sway of “the beast” in whatever form that might take.

The beast, or antichrist if you want to call it that, is simply any powerful system or individual that sets itself in opposition to the way of Christ by falsely promising us peace, wealth, and security while simultaneously demanding our unswerving loyalty. It is anything that tempts us to trust in it for our ultimate well-being rather than Christ. In the world in which Revelation was written, the beast took the form of the Emperor and the Roman imperial system. Throughout history we can think of other possible examples, but poignant recent examples could be figures and systems like Hitler/Nazism, Soviet era communism, the authoritarian cult of reverence for the Kim family in North Korea, China’s government, or the surveillance state that Peter Thiel is apparently unwittingly helping to architect while Elon Musk develops chips to put in your brain. I also think of a particular political figure who in recent years has amassed a cult-like following, leading large numbers of Christians to place their trust in him to restore his country to its supposed former glory, to “save Christianity” even though he himself has said he hasn’t ever felt the need to ask God’s forgiveness for anything despite spending a lot of time with a particular financier with a taste for underage girls. I won’t name him, but like the author of Revelation I will say his number is 45 and 47.

All of the above examples bear “beast-like” qualities to some degree or another, and some obviously more closely resemble the beast archetype than others. Still, the message of Revelation, when it comes to the beast/antichrist is always to call us to ultimate loyalty to Christ and his kingdom because there are always systems at work in the world that oppose it. This could take the form of nationalism or the growing AI dominated techno-surveillance state. As the letter of John says, “many antichrists have come.” But will there be some ultimate figure or system who rises up and precedes the second coming of Christ? Perhaps. But the point of Revelation is not to give us coded predictions of current world events, but to call us to faithful living in the present, to be willing to say no to those worldly figures and systems that falsely promise to give us the things that only Christ is truly able.

Great post! After I left behind dispensationalism, the view you articulated made so much more sense. And yet, I was challenged by something John Stott wrote in his 2 Thessalonians commentary: "Yet all these, together with evil leaders down the centuries, have been forerunners or anticipations of the final 'man of lawlessness,' an eschatological yet historical person, the decisive manifestation of lawlessness and godlessness, the leader of the ultimate rebellion, the precursor of and signal for the Parousia. I agree with Geerhardus Vos that 'we may take for granted. . .that the Antichrist will be a human person. And whether we still believe in the coming of Antichrist will depend largely on whether we still believe in the coming of Christ." I'm not sure I agree with him but it's stuck with me.